CRC TRR 228 Activities

Wawili Toolbox

Scientific toolbox of the Tandem Project ‘Mtu ni Watu – Disclosing Hidden Stories of Fieldwork’.

Toolbox Summary

We would like to present the scientific toolbox of the Tandem Project ‘Mtu ni Watu – Disclosing Hidden Stories of Fieldwork’, funded by the Cologne International Forum. The title ‘Mtu ni Watu’ refers to the Kenyan proverb ‘a person is people’, indicating that we never achieve a goal alone, but that our work is always situated in a broader social context. This is especially the case in anthropological fieldwork in which researchers try to explore a topic in an often unknown cultural context for a long period of time. The immersion into this cultural context is an essential element of anthropological research and usually accompanied by one or more assistants. These assistants not only assist and interpret language during fieldwork, but also act as cultural brokers, guide researchers in their daily struggles, manage the complexities and challenges of fieldwork, and counsel in critical situations. Moreover, many assistants also become associates and co-producers of the scientific knowledge acquired during research. Research assistants, therefore, have a high status in anthropological work, and their lives are impacted upon by anthropologists. Yet their perspectives and experiences in fieldwork, that have great potential to enrich anthropological work, are little reflected in those publications that emerge from the work they ‘assist’.

Our project aims to accomplish two tasks that shift the focus away from the researcher and towards the perspectives of our assistants, focusing on their stories and perceptions of research.

The Wawili-Toolbox (named after the proverb: ‘Wawili hula ng’ombe’ – two people can manage to eat a cow – which symbolises the exigency for assistance in academic fieldwork) is an instrument designed to capture the results of the project on a scientific level. We intend to publish short stories and reflections of all participants – assistants, researchers and members of the local communities – allowing current and future generations of researchers to reflect on the character of and the decolonial critique towards collaboration/cooperations/partnerships between the Global South and the Global North, providing guidance on how to initiate partnerships and reflecting ethical challenges of our work. The blog entries shall cover all sorts of relations and interactions, from the beginning to the end of the project, and beyond.

In the following, you can explore the stories of two different research teams. Betty, Francis and Richard work in Kajiado County in southern Kenya. In the vicinity of the Amboseli National Park and in the context of conservation, farming and pastoralism among Maasai people they conduct research on the socio-ecological transformations in the region. Kudee and Peter are the members of the second team and work in Baringo County in the north-west of Kenya. They especially reflect on the fieldwork undertaken in 2014 and 2015 in the pastoral landscapes of Pokot people.

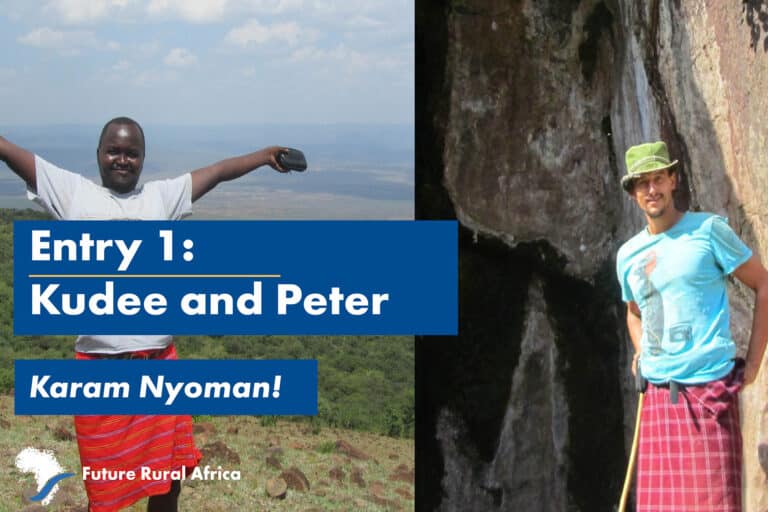

Entry 1

Karam nyoman!

We would like to introduce ourselves: Kudee and Peter. As one of the two teams participating in the ‘Mtu ni Watu’ project, we would like to present our common story of research, life and work in East Pokot between 2014 and 2015. You may know us by other names, such as Charles, Hauke, Losiwanyang, Rionokou, Scholes, and a few others. Here we wish to write under those names we had in the community at Mt. Paka, the region where we collectively conducted research.

Entry 2

My name is Richard Kiaka. I am an anthropologist researching on a wide range of topics, especially on community conservation. I did fieldwork for my Ph.D. research amongst the Damara people of northwest Namibia in a community conservancy called Khoad Hoas. My work benefited a lot from the support of my local research assistants from the community I worked in. From 2021, after I relocated to Kenya, I started working with Maasai people on research projects in the Amboseli ecosystem in southwestern Kenya. There, I met Francis Nkadayo and Beatrice Taiko who have worked alongside me as research assistants. Before getting deeper into our research experience, it is nice that Francis and Betty should introduce themselves.

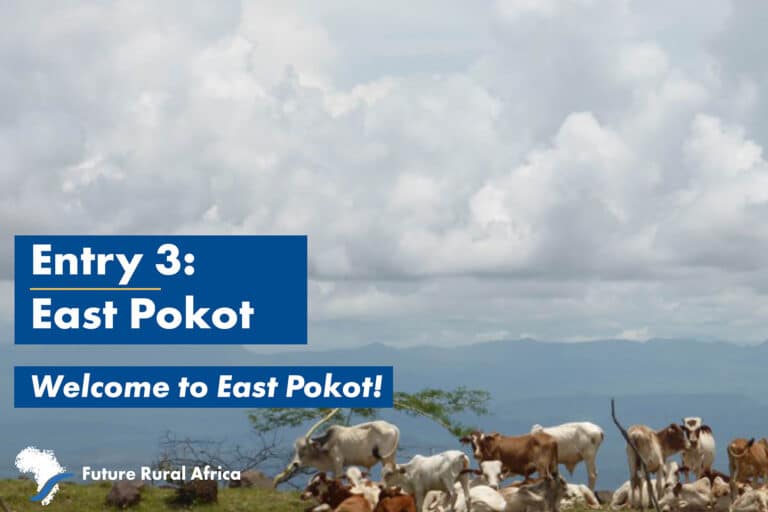

Entry 3

East Pokot

What’s East Pokot? East Pokot is a region named after a group of people called Pokot who live in Kenya. It’s a pastoral community with a nomadic lifestyle in the north-western parts of Kenya. The region lies in the Rift Valley and the Pokot people have a rich culture centred around their livestock. More generally, Pokot territory can be divided into Pokot West, South and North, but East Pokot is rather marginalized compared to the other regions, in terms of government development and also education. So, that’s East Pokot. (Kudee, 1 February 2024)

Entry 4

The Amboseli ecosystem is the land that surrounds the Amboseli National Park found in south-western Kenya along the Kenya-Tanzania border, and lies on the northern steppes of Mount Kilimanjaro. The name Amboseli, comes from a Maasai word, ambosel, meaning salt dust that dominates the area. In the Amboseli, vegetation consists of grassland, woodland, bushland, and swamp habitats which are variously utilized by both communities and wild animals. Amboseli is generally semi-arid with annual rainfall averaging 586mm. The aridity is aggravated by climate change, that frequently leads to death of livestock and water-dependant wild animal species, causing livelihoods challenges to thousands of households.

Entry 5

When does research actually start? As a doctoral candidate, you don’t just hop on a plane, arrive in Kenya, travel to the research region, and get started. Usually, the Ph.D. begins with thorough preparations at the university, the application for the required documents in the field, possibly a shorter exploration trip to the region (hopefully together with some colleagues), discussing the topic, and thinking about the actual location of your fieldwork. Before Peter knew that he would conduct research at Mt. Paka, more than six months of preparation had already passed, and six more would pass before Kudee and Peter moved into their hut in Paka. But how, actually, did the two meet for the first time?

Entry 6

he arrival at Mt. Paka and life among the pastoral community is something that will be explored below. Of course, in retrospect, many experiences appear in a new light when you know the story has a happy ending. But especially the beginning of fieldwork and living among a new community remains an exciting and difficult endeavour.

During the first few months, Kudee and Peter were not always convinced that their fieldwork was going in the ‘right’ direction. When the initial, uncomfortable period of living in their tent was over and they moved into their new hut, they had to make some further decisions.