By Johannes Dittmann (Project C03 Green Futures).

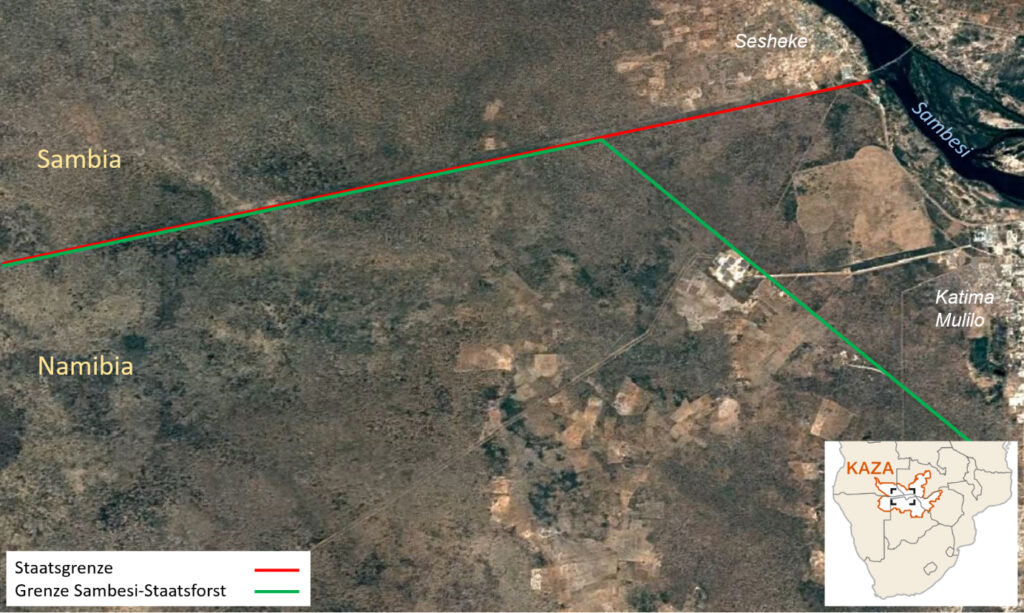

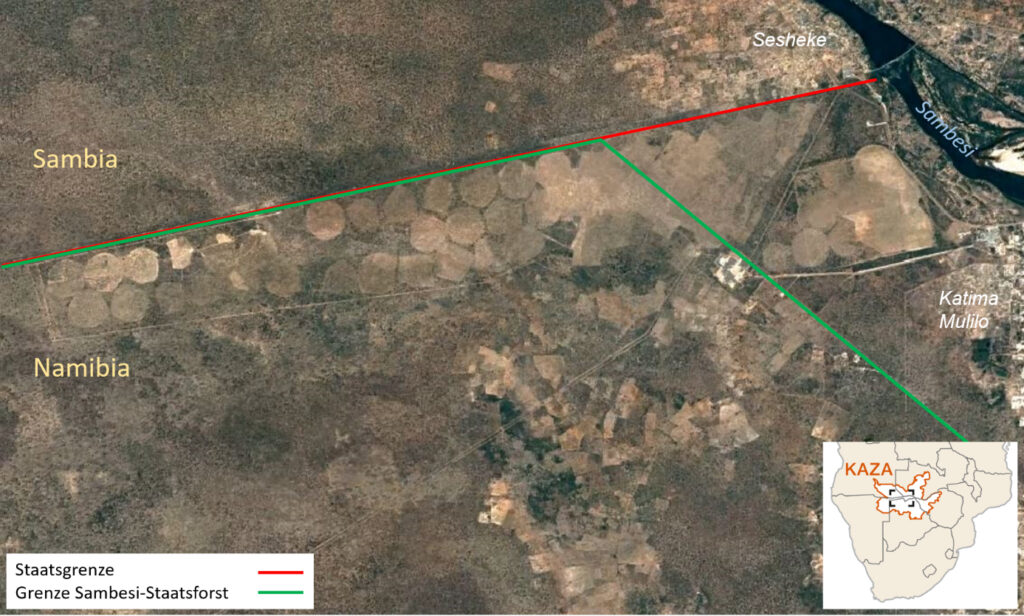

Between 2017 and 2020, a conflict between the then Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry (MAWF) and the then Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET) over the use of the Zambezi State Forest (better known by its old name, Caprivi State Forest) attracted political and public attention in Namibia. The conflict started when the MAWF approved the logging of large areas of the State Forest in 2017 to establish an agricultural irrigation scheme (called Green Scheme). The MET argued that the State Forest is a protected area of international importance and should not be logged because of its role as a wildlife corridor of the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area.

The Green Schemes in Namibia date back to an initiative of the Bantu Investment Corporation, which was founded in Pretoria in 1959 (I17). Under the leadership of the apartheid government, this South African company had the task of increasing investment and economic growth in the Bantu reserves in South Africa and its protectorate of South West Africa (today Namibia) through various development programmes. As part of these programmes, irrigation projects were planned in in the north-eastern part of South West Africa from the 1960s onwards to intensify agricultural productivity. After Namibia gained independence in 1990, these irrigation projects were heavily subsidised under the name ‘Green Schemes’ and promoted by Namibia’s agricultural ministry. Today, Namibia’s Green Schemes are coordinated by the state-owned company Agricultural Business Development Agency (Agribusdev), which pursues the aim to make a decisive contribution to Namibia’s food security by increasing agricultural productivity (GRN 2008; I17; I26; I01). The export of agricultural products is a secondary objective. According to one of the programme’s senior staff and co-authors of the Green Scheme Strategy (GRN 2008), the Green Schemes also had a political purpose under the South African mandate government. Like many other projects of the Bantu Investment Corporation, they served to consolidate the state’s presence and sovereignty in peripheral regions on the one hand, and to legitimise the internationally contested mandate claim over the so-called Bantu Reserves on the other (I17). Before 1990, they were part of a strategy to demonstrate South Africa’s efforts for economic growth in the Bantu Reserves through a development programme (ibid.). Today, the Green Scheme projects are supposed to represent the Namibian government’s commitment to greater food security in the form of technologized agricultural structures. The Green Schemes persist despite massive allegations of mismanagement and corruption (Namibian Sun 03.03.2021; The Namibian 19.06.2020; The Namibian 25.07.2019; The Namibian 08.10.2019; The Namibian 15.10.2019) through heavy subsidies because they function as political prestige projects.

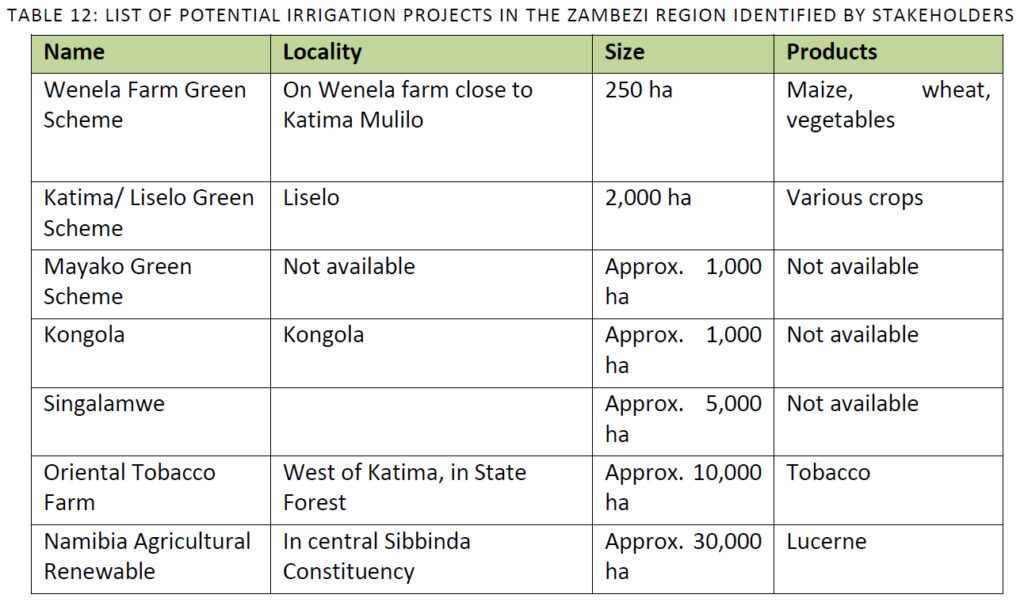

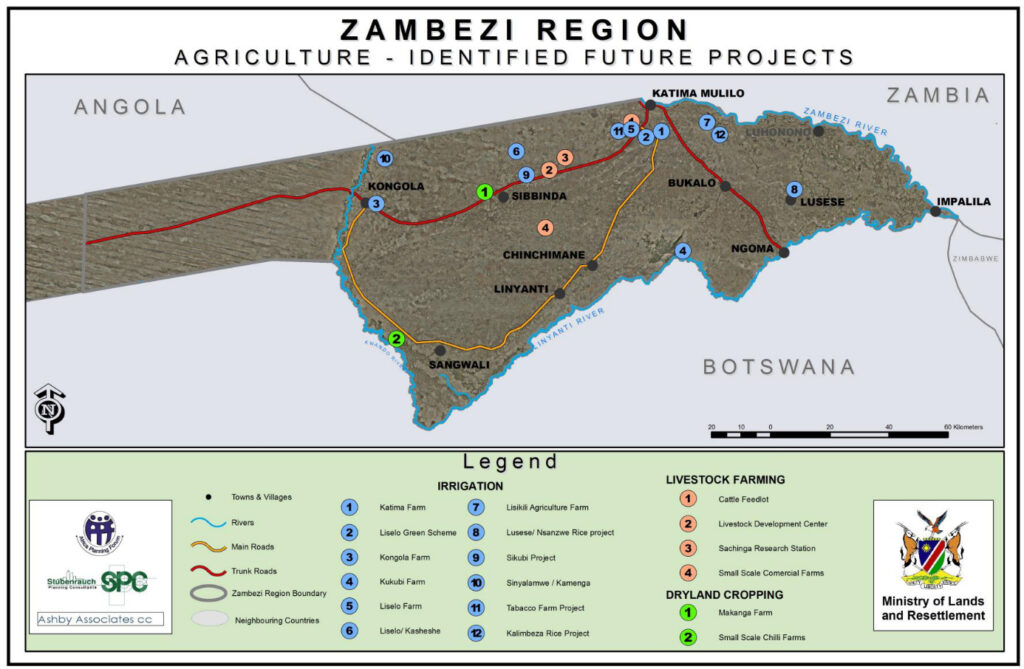

In the Zambezi Region, only one Green Scheme was established, the Kalimbeza Rice Green Scheme, which lies east of Katima Mulilo near the Zambezi River. In the early 2010s, the then Permanent Secretary of the MAWF, Andrew Ndishishi, began entering into lease agreements with Traditional Authorities on behalf of the government in order to secure more land for Green Scheme projects. Since then, Green Schemes have increasingly become central to the vision of north-eastern Namibia as the country’s breadbasket which is promoted by the agribusiness sector (Namibian Sun 28.04.2017; I17: I01). In February 2020, Governor of the Zambezi Region Lawrence Sampofu promoted more investment in Green Schemes. According to Sampofu, the programme needs funding of one billion Namibia dollars (about 57 million euros) to make the Zambezi Region the breadbasket of the country (Namibian Sun 27.02.2020). The Zambezi Regional Land Use Plan (GRN 2015b) lists seven potential irrigation projects with a total area of 49,250 ha (see Fig. 16). On the corresponding map of the land use plan (Fig. 17), as many as 11 potential irrigation projects are shown.

As can be seen in Figure 17, the locations of the planned irrigation projects 3, 5, 6, 9, 10 and 11 are north of the Trans-Caprivi Highway. This area between Kongola in the west, Katima Mulilo in the east, the border with Zambia in the north and the Trans-Caprivi Highway in the south is the Zambezi State Forest. In 2014, in cooperation with the then Minister of Lands, Utoni Nujoma, local Mafwe Traditional Authorities pledged to the MAWF the use of an area of about 10,000 ha for 25 years for irrigated agriculture after a feasibility study by the Namibian consultancy Nyepezi Consultancy endorsed the establishment of a Green Scheme (New Era Live 12.10.2015; Namibian Sun 04.01.2018). To clear the land, the MAWF contracted the Chinese state company Namibia Oriental Tobacco CC, which planned to grow tobacco for export to China. Parts of the forest were to be cleared in order to construct the irrigation areas (Namibian Sun 21.06.2019).

Various actors from the health sector, the organisation for landless people (Affirmative Repositioning) and activist youth groups organised a public movement against the Green Scheme project, criticising in particular the planned cultivation of tobacco for export instead of food for the domestic market (News24 10.03.2015; The Namibian 19.06.2019). In interviews, representatives of the Katima Mulilo Regional Council and the Namibia Agronomic Board were also sceptical about the planned irrigation scheme in the Zambezi State Forest, as the Green Scheme Strategy is geared towards the cultivation of grain and vegetables (GRN 2008; I71; I75; I54).

Representatives of Namibia’s environmental sector saw in the planned Green Scheme as a threat to the ecosystems of the Zambezi Region claiming the location where the irrigation project was to be established a protected area (B13; I79; I55). When reports about the first clearings for the establishment of irrigation areas in the forest were published by Namibian print media in 2017, political resistance against the Green Scheme was formed among various environmental actors. The MET and various conservation NGOs described the logging in the state forest as illegal, uneconomical and harmful to the environment. Various conservation experts explained in interviews during fieldwork that the state forest fulfills important ecological functions for the entire region of the KAZA TFCA, as it serves, as a refuge and migration corridor for various wildlife species. As an advisor at the MET explained:

“The state forest is quite important. In the KAZA concept, six so-called Wildlife Dispersal Areas are defined and one of them is in the Kwando region, because this is the main wildlife corridor from south to north. And the Zambezi State Forest is part of it” (I04).

Representatives of the Namibian KAZA-coordination and other conservation institutions stated in interviews that the Green Scheme, and in particular the deforestation for its establishment, contradicts the KAZA vision (I04; FT01; I65; I55). The opposition of the conservation sector was particularly supported by the influential consultancy Namibian Chamber of Environment (NCE). In a public statement the NCE highlights the importance of the state forest to KAZA:

“The value of these woodlands to Namibia include providing a landscape that is attractive to tourists, particularly in the KAZA Transfrontier Conservation Area where Namibia has made an international commitment” (NCE 2019, pp. 1- 2).

Forestry experts the NGO sector explained in interviews that the ecosystem in the state forest would be permanently destroyed by the clearing because the specific tree species take on ecological functions that can only be restored after several decades or even centuries due to the slow plant growth in the semi-arid climate of the region (B08; M04; I40; I48). A former employee of the Directorate of Forestry (DoF) (then part of the MAWF) explained in an interview that although the forest area is called ‘state forest’ and shown on maps as a protected area, there is no legal basis for this status (I34). Research by a legal expert of a local conservation NGO concluded that no document could be found designating the Zambezi State Forest as a protected area:

“I was contracted by the environmental ministry to assess the legal status of the state forest. People just called the area state forest but in fact the legal status is unclear. We looked everywhere but there are no legal documents declaring it as a state forest – that was the loophole” (FT01).

The establishment of the Green Scheme project in the state forest therefore did not directly violate nature conservation laws, though the MET claimed the opposite. Based on the Namibian Forestry Act (GRN 2001), the MAWF issued several concessions for logging in the state forest through the DoF. Environmental minister Pohamba Shifeta accused agricultural minister Alpheus !Naruseb in 2018 of ignoring the Namibian Environmental Management Act (GRN 2007a) in the process, which requires environmental impact assessments to be conducted by the MET for the issuance of logging concessions. According to Shifeta, the logging was illegal because the environmental impact certificate on file for the Green Scheme was invalid (THE VILLAGER, 30.10.2018). According to a local conservation consultant, this environmental clearance certificate for the Green Scheme should not have been issued:

“The environmental clearance was finally granted for the project but the environmental impact assessment was inadequate. It had been rushed through, it didn’t look at all the issues, it was going to take a large part of the state forest which is actually an important corridor for wildlife movement […]. And that wasn’t being adequately recognised […]. The impact assessment was particularly negligent about social issues. […] I mean that shouldn’t have got its clearance” (I55).

A conservation expert who used to work in the DoF told in an interview with the author that the DoF overlooked the invalid environmental impact assessment when granting concessions. The unclear status of the environmental impact certificate and the distributed concessions was only one of the reasons why the Green Scheme project increasingly appeared legally questionable. Widely varying statements were made in the media by different members of the MAWF regarding the planned size of the area, the exact location and the boundaries of the Green Scheme (M04). Furthermore, logging was coordinated by the DoF without informing other ministries or organisations. In a short period of time, providing vital corridors and connectivity for wildlife across landscapes – the entire five-nation Kavango-Zambezi (KAZA) Transfrontier programme is dependent on connectivity […] large areas in the state forest were cleared, the tree trunks were removed and journalists or other independent actors were evicted from the cleared areas. The MAWF claimed that the logging was legal (The Namibian 17.12.2018) and did not provide more detailed answers to media enquiries (The Namibian 13.03.2019). Several experts interviewed expressed the suspicion that the unclear legal framework and withheld details on logging in the state forest were intentional ambiguities:

“It is chaos and people take advantage of that. As long as you leave it as chaos it is more easy to benefit. It is chaos by intention” (expert on environmental law, FT01).

“I think the directorate of forestry is sleeping. But there were also a lot of rumours about fogging handshakes” (forestry scientist, M04).

“I am not accusing but it can be a deliberate oversight because people get paid from corruption” (NGO member, I44).

Suspicions of corruption increased as it became clearer that the economic interests behind the clearing of large areas of state forest were not so much the establishment of a irrigation scheme, but the sale of desirable timber species such as pterocarpus angolensis (or kiaat) or baikiaea plurijuga (or Zambezi teak), often summarized as rosewood. Although the selected clearing sites were cut into the area in a circular pattern (see Fig. 18), as is customary for certain forms of irrigated land, the sites were not selected for their potential for agriculture, but for the occurrence of those species, as confirmed by staff of the MET (I65; I75).

The concessions for logging in the state forest were granted by the DoF to local elites of the Mafwe Traditional Authority, who sold them to the companies Uudenge Investments CC and Okatambo Investments CC (FORDRED 2018; The Namibian 10.07.2017). The transport of the logs was organised by the Chinese logistics company New Force Logistics CC, which provided the link to the demand for rosewood in Asian markets. The logs were transported roughly cut to size on trucks from the Zambezi Region to Walfis Bay (Namibia’s deep-sea port) and from there transported in containers to primarily countries in Asia.

By this, the actors involved, i.e. the DoF or the Ministry of Agriculture, New Force Logistics CC as well as the local Mafwe elites and timber workers, violated the national Forestry Act of Namibia (GRN 2001), which prohibits the sale and export of raw timber from Namibia. In addition, the head of New Force Logistics CC, Hou Xuecheng, who was already known in Namibia for the illegal trade in ivory and other wildlife products, tried to deceive the Namibian authorities by mixing Namibian rosewood with rosewood harvested in Zambia (Oxpeckers 09.08.2017). Journalists also reported that political elites in the Ministry of Agriculture were personally enriched by the rosewood trade (ibid.). According to experts interviewed, the logging in the Zambezi State Forest was never about establishing a green scheme (I04; I31; I26). Rather, it was a deal between local elites, various Namibian authorities and businessmen from Namibia Oriental Tobacco CC and New Force Logistics CC, aimed at exporting rosewood from the beginning (ibid.). An employee of a Namibian agribusiness explained the case as follows:

“There was a big thing last year about whether the Chinese would build up a big tobacco plantation up there in the state forest. And this was apparently going ahead. And then there was speculation. Obviously they were only interested in the forest. Because the area isn’t suitable for tobacco plantation at all. But in order to do the tobacco plantation […] they were going to clear the area of the forest and then use the timber and then probably say: ‘Oh no look the tobacco doesn’t want to grow’. But by then they already had messed up” (I26). According to a journalist who intensively investigated the rosewood scandal between 2017 and 2019, Chinese traders made the most profit in the logging operations, buying the logs cheaply from local elites and selling them at a much higher price in Asia:

“The Chinese are basically converting worthless currency into a high value asset at an enormous profit […] by exploiting a weakness in the system. Like this previously unused permit system (of the DoF) to buy trees for like 20 dollars from a local chief but you know he (trader) is buying thousands of those because he has money to export it. And then in China it is worth that 200 times minimum.” (I31)

According to the newspaper The Namibian, woodworkers get about 20 Namibia Dollars (NAD) (about €1.20) for a rosewood tree from the Traditional Authority. The Traditional Authority sells them to the Chinese trader for about 350 NAD per piece (€20.50). This trader in turn receives about 5,000 NAD (€293) per tree trunk on the Asian market. In 2019 e.g., the trader paid about 210,000 NAD (€12,317) to the Mafwe-Traditional Authority for a shipment of 600 logs of rosewood and sold them on the Asian market for more than 3 million NAD (about €176,000) (The Namibian 01.03.2019). “We are exporting them literally for free,” the Permanent Secretary of the MET said in an interview with the Namibian Sun newspaper (Namibian Sun 12.07.2019). Between 2015 and 2019, 225 containers of rosewood were exported to China via Walfis Bay, with a peak of 208 containers in 2019 (The Namibian 08.03.2019). This equates to a total weight of approximately 11,700 tonnes. In 2017, 3,762 t of rosewood was also exported to Vietnam and a further 640 t to France. These figures also include rosewood harvested in Zambia, for which Walfis Bay was used for export. How much wood came from Namibia can no longer be fully reconstructed (ibid.). In conversation with the author, a Namibian forestry expert estimated that 60,000 trees with a trunk diameter of at least 45 cm were removed from the Zambezi State Forest in 2018 alone (B08). On the Asian rosewood market, this amount of trees would have a value of €17,580,000 according to The Namibian’s calculation (01.03.2019).

The Director of the DoF has been accused by conservation organisations of preventing to stop illegal logging in the Zambezi State Forest or even personally profiting from the export of raw timber (Oxpeckers 09.08.2017). Interviewed forestry experts explained that the unclear communication by the DoF and the MAWF was a deliberate strategy to conceal illegal logging (I61; I33). A journalist in Windhoek, who investigated the logging, stated in an interview that the case was a corruption scandal initiated by several leaders of the MAWF and the Ministry of Land Reform (MLR) in collaboration with Chinese companies (I31). In one of his reports he states:

“The political driving force behind the whole operation is Chinese investment to the tune of $14 billion Namibia dollars to establish a 10,000 ha tobacco farm west of Katima Mulilo. It was initiated by politicians in key positions such as the land reform minister Uutoni Nujoma and Swapo organiser Armas Amakwiyu – and against all odds, but with the approval of the local traditional Mafwe authority” (Grobler 2017, p. 22).

According to the journalist’s research, several officials in top positions in the MAWF personally benefited from the logging by facilitating the transport of the tree trunks to Walfis Bay. Due to their internal network structures in the ruling party, these political elites were even somewhat protected from Namibian law (I31) and have not been arrested to date, despite the fact that independent journalists (Oxpeckers 09.08.2017), Namibian newspapers, legal experts from the Namibia Legal Assistance Centre (FORDRED 2018) and the Namibia Anti-Corruption Commission (Namibian Sun 06.03.2017) investigated and provided ample evidence of the illegal logging and transaction of logs. Only the head of the logistics company, New Force Logistics CC, and a customs officer were convicted of corruption in early April 2019, but were released on bail (The Namibian 03.04.2019).

Due to the lack of a processing industry, hardly any value can be created in Namibia through the felling of trees, so that the sales prices for raw wood remain relatively low at around NAD 350 per tree (€20.50). According to some of the experts interviewed, monetary motives alone cannot be regarded as the driving force behind deforestation (I40; I26; I34). Various actors claimed land rights in the state forest in the course of establishing the Green Scheme. According to the experts involved, these actors included local elites of the Mafwe-Traditional Authority as well as people in leadership positions of the MAWF (ibid.; I65; FT01), who see themselves as descendants of communities that were expelled from the area in the middle of the 20th century when Namibia was still a South African mandate territory (I26; I34).

Interviews with DoF staff confirm that logging in the Zambezi State Forest was a politically sensitive issue. One staff member kept a very low profile in the interview and recommended that the author contact his superiors for further information (I42). Another DoF staff member was also reluctant to comment on the issue, saying that statements about logging in the state forest could possibly have negative consequences for her personally:

“You see […] this ministry we are sitting in is the Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry. So I really don’t want to give a political statement about that (logging in state forest). Because they could tell me afterwards that I am no longer part of this ministry” (I71).

In the public discourse, the role of the MAWF in logging was increasingly questioned in 2019. In particular, the MET and other conservation organisations questioned the DoF’s actions (see Figure 19) (Namibia Economist 04.03.2019). The debate on the forest manifested a long-standing controverse between the ministries regarding responsibility for forestry, which has its origins in the formation of a new government after the 2004 presidential elections. When President Hifikepunye Pohamba took office in 2005, the government was restructured and the DoF, which until then had been part of the MET, was transferred to the MAWF (The Namibian 10.11.2005). Since then, DoF initiatives were often perceived as encroaching on the MET’s spheres of authority, partly because community based conservancies (coordinated by the MET) and protected community forests (coordinated by the DoF) overlap spatially and follow very similar management approaches (I24). The MET considers forestry as part of its own area of responsibility and can exert influence on the management of forests through the national Environmental Management Act (GRN 2007a). When the MAWF contravened the national Forestry Act (GRN 2001) in the course of logging in the Zambezi State Forest, it left itself open to legal challenge (The Namibian 10.04.2019). Through this route, in March 2019, environmental minister Shifeta instituted a general moratorium on commercial logging in north-eastern Namibia and instructed local police in the Kavango and Zambezi Regions to arrest those involved in logging. This was not directly within his remit, nor was a blanket ban on the issuance of logging concessions by the DoF, which he issued back in November 2018. There was a political rift between the ministers, various directors and other actors of the two ministries, which was also played out in public, as experts interviewed confirmed:

“There is an issue concerning logging in the state forest of Zambezi-Region by Chinese. As this is the jurisdiction of forestry but the forest is in the KAZA TFCA there are disputes between the environment ministry and the agricultural ministry and in particular between the ministers” (I20, legal expert of a local NGO).

“There has been very poor communication between the directorate of forestry and the environment ministry so much so that the minister of environment started putting moratoriums on logging which arguably doesn’t fall under his jurisdiction. There is such a lot of outcry that someone had to do something but the agricultural ministry was silent on the issue” (I38, legal expert of a local NGO).

Among the critics of deforestation, the NCE was particularly prominent (NCE 2019). In an interview with The Namibian newspaper, its CEO described minister of agriculture as “useless” and “inactive” (The Namibian 12.04.2019). During a conference on ecosystem services in Windhoek in 2018, which the author attended, a member of the NCE and a representative of the DoF were present. At the event, the member of NCE accused the DoF representative that his superior was not doing anything to stop deforestation:

NCE: “There is large deforestation in the Zambezi region. It is such an important part in context of KAZA and climate change adaptation. The ministry of environment is defending the forest from the minister to the bottom. But the director of forestry is doing nothing about it!”

DoF: “The two ministers currently argue about the case of Zambezi region. There might be some issues with that single case but overall the Namibian forests are doing very well” (B02).

The official of the DoF justified the (in)activities of his directorate by playing down the deforestation in the national forest.

The conflict over the state forest not only caused controversies between the ministries, but also divergences within the DoF. In interviews with the author, staff members at lower hierarchy levels took a position different from that of the directorate’s leadership. In their opinion, logging is a threat to the forests because it does not follow a conservation approach but purely commercial motives. In interviews, they distanced themselves from logging in the Zambezi State Forest:

“I definitely consider myself more a conservationist than an agriculturalist. I am dedicated to the conservation of forests. In Namibia we don’t do a lot of processing of wood […] In fact most of the activities we are carrying out we do them together with the ministry for environment” (I71, DoF staff member).

“We are not encouraging timber production. We primarily work on the non-timber benefits of forests because there are a lot of ecosystem services. Namibia is a dry country so it is not sustainable to cut trees. We promote pole production which includes maintaining the tree” (I42, DoF staff member).

The statements of the DoF staff members contradict the attitude of the directorate’s leadership. The DoF office in Katima Mulilo was not involved in the deforestation and was even informed about the incidents by the regional office of the MET and not by the MAWF (I65). This suggests that the conflict over the Zambezi State Forest was also characterised by internal problems within the MAWF. An interviewed forestry expert sees these internal problems as being particularly rooted in conflicting objectives between the DoF and the Directorate of Agricultural Production, Engineering and Extension Services (DAPEES), which is also based in the MAWF:

“Just scan the abstract of the Forestry Act and compare it with agricultural policies. […] The policies of agriculture advocate for greater clearing of forests but the forestry policies actually want to keep the forests. Such tensions just confuse the whole issue […] So people don’t speak the same language there […] Forestry fits very well in the environment ministry because they speak the same language […] So there are those clashes within the ministries between the different directorates” (I48).

An employee of the MET also stated in an interview that the activities and goals of the DoF and the DAPEES contradict each other (I79). In his opinion, the DoF should be part of the MET in order to avoid contradictions and overlaps between the ministries (ibid.). Employees of the DoF themselves demand that it be reassociated with the MET: “It is the directorate (of forestry) itself which is saying that they do not belong there and that their functions are not understood where they are” (I79). Agriculture has a higher political priority in the MAWF than forestry. Accordingly, the recommendations of DAPEES on deforestation for the establishment of a Green Scheme are enforced, even if representatives of the DoF are of the opposite opinion. An interviewed forestry expert described the relationship between the directorates as follows: “I think the directorate of forestry is just the puppet of the directorate of agriculture because from the minister’s side agriculture always goes first! (M04).

Unlike their staff, the DoF’s leadership does not have a conservation-oriented perspective on forests. According to a conservation NGO member, the DoF leadership saw forests more as economic resources even when they were still part of MET and before they were integrated into the MAWF: “The heads of the DoF always looked at themselves to be part of agriculture and looked at forests in terms of agricultural products like timber” (I44). For this reason, and because of party-political motives by which a former director of the DoF wanted to underpin his independence from the MET, there were strong tendencies at the leadership level of the directorate to affiliate with the MAWF in 2005 (ibid.; I40). According to an interviewed forestry expert, the successor of that director continues this perspective on forests and on the MET to this day:

“There were strong efforts at that time […] to actively spin off the DoF from the MET, i.e. there was also a self-initiative to emphasise precisely this independence. The first director of Forestry was more or less the mentor of the current director. And much of the thinking was passed on in the sense that the MET is not necessarily regarded as the beloved big brother” (I40).

By the time a ban on the clearing and export of raw timber from Namibia came into effect on 31 March 2019 through the initiative of the MET, the logging of rosewood had already spread to other areas in north-eastern Namibia. Local elites in Rundu (Kavango East Region) became aware of corresponding stands in areas west of Khaudum National Park through the link to rosewood demand created by New Force Logistics CC, and acquired logging concessions from the DoF (The Namibian 01.03.2019). These elites included members of the Namibian parliament, ministries, local councils, police and clerical institutions, who wanted an estimated 200,000 trees cut on their land parcels (known as Small Scale Commercial Farms or SSCFs) (ibid). Most of these SSCFs are located in the area between Mangetti National Park and Khaudum National Park, which is considered a significant wildlife corridor in the context of the KAZA TFCA, similar to the Zambezi State Forest. The Rundu elites publicly accused the minister of MET of tribalist views and exerted political pressure on the government through the MAWF. They threatened that the ruling SWAPO party would lose votes from the Kavango East Region in the next presidential elections in November 2019 if the logging ban remained in place (ibid; Namibian Sun 28.06.2019). President Hage Geingob then took action. In September 2019, he lifted the ban on rosewood exports again, on the grounds that several tonnes of already felled trees were rotting unused in the Zambezi and Kavango Regions (The Namibian 19.09.2019). Timber that had already been felled was then allowed to be transported and exported again. The logging of further tree stands remained prohibited. At a party event in November 2019, President Geingob made an active call to sell the timber that had already been cut:

“I am announcing today that those timber that have been cut and is rotting must go. In the future we are going to have a proper way of having factories to produce furniture here. But it’s already cut, it’s on the ground, lying there rotting, sell that anywhere you can” (Namibian Sun 04.11.2019).

This reaction of the president shows to what extent power-political processes within the Namibian government shape the conflict over the Zambezi State Forest. Prior to 2015, the Green Scheme project in the Zambezi State Forest had already been proposed several times by the MAWF, but had not been approved in the then government cabinet (Pohamba II). The first government cabinet of president Hage Geingob (2015-2020) also initially did not give the Green Scheme a commitment because Armas Amukwiyu, SWAPO politician and shareholder of Namibia Oriental Tobacco CC, ran against President Geingob’s favourite at the SWAPO party congress in 2017 and in the course of which he could no longer hope for government leadership support for his company (Namibian Sun 20.06.2019). However, shortly after, the Green Scheme in the state forest was approved, largely because the MAWF announced that it would create 7,120 permanent jobs with the establishment of the irrigation scheme (Namibian Sun 21.06.2019). In early 2019, logging in the Zambezi State Forest was at its peak (I44). According to a legal expert at the Namibian LAC, it was tolerated by government leaders because they feared losing votes for the 2019 presidential election by placing a moratorium on logging:

“Most politicians think in five-year cycles and this is an election year (2019). And during an election year there are a lot of promises about creating employment and money. So that may answer the question why after a long time this project (green scheme) has finally been granted in cabinet” (B08).

The political conflict between and within the ministries over forest areas in north-eastern Namibia led to the restructuring of Namibian government institutions. With the beginning of president Geingob’s second term in 2020, the DoF was moved to the MET, which is since being called the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT). The director of the DoF remained in office and agreed with the director of the Directorate of Wildlife and Parks in MET to officially designate the Zambezi State Forest as a state protected area (I71). The until then minister of agriculture Alpheus Naruseb left office and also resigned as a member of the Namibian parliament. The agricultural ministry of Namibia (until then Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry (MAWF)) was joined by the Ministry of Land Reform (now Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Land Reform (MAWLR)).

In 2020, an estimated 120,000 rosewood logs were still exported from the Kavango and Zambezi Regions to Asia. The transport was still organised by New Force Logistics CC (The Namibian 03.02.2020; Namibian Sun 24.02.2020). According to a report by the Organised Crime and Corruption Report Project, rosewood trees were still being cut in the Kavango East Region in 2020, particularly on the land of SSCFs (OCCRP 18.12.2020).

Increased demand for rosewood in Asian markets since 2017 has put at risk various forests in the KAZA region that are refuges or passage areas for various wildlife species, according to the international organisation Trade Records Analysis of Flora and Fauna in Commerce (TRAFFIC) (Lukumbuzya & Sianga 2017; Knott et al. 2019). Namibia is just one example of the problem of rosewood logging, which takes place in several countries on the African continent and is classified by TRAFFIC as environmentally damaging and mostly illegal (ibid.).

References

Click here for all references

FORDRED, A. (2018): Rosewood harvesting and export in Namibia. Presentation by intelligence-i1. (Namibia Scientific Society), September 2018, Windhoek.

GRN (GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA) (2001): Forestry Act 12 of 2001. (Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry), Windhoek. Available from: www.lac.org.na/laws/annoSTAT/Forest%20Act%2012%20of%202001.pdf, [08.06.2023].

GRN (GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA) (2007): Environmental Management Act 7 of 2007. (National Planning Commission), Windhoek. Available from: www.lac.org.na/laws/annoSTAT/Environmental%20Management%20Act%207%20of%202007.pdf, [08.06.2023].

GRN (GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA) (2008): Green Scheme policy. (Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry), Windhoek.

GRN (GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA) (2015a): Kavango East Integrated Regional Land Use Plan 2016-2026. (Ministry of Lands and Resettlement), Windhoek.

GRN (GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA) (2015b): Zambezi Integrated Regional Land Use Plan 2016-2026. (Ministry of Lands and Resettlement), Windhoek.

GROBLER, J. (2017): Geraubter Staatsforst. In: Afrika Süd, no. 6/2017, p. 21-23.

KNOTT, K., KNOTT, A. & NEWTON, D. (2019): A critical assessment of the economic and environmental sustainability of the Namibian indigenous forest/ timber industry. (TRAFFIC East/Southern Africa), Pretoria. Available from: www.traffic.org/site/assets/files/12756/namibia-timber-final-vweb.pdf, [08.06.2023].

LUKUMBUZYA, K. & SIANGA, C. (2017): Overview of the timber trade in East and Southern Africa: National perspectives and regional trade linkages. (TRAFFIC and WWF), Cambridge. Available from: www.trafficj.org/publication/17_Timber-trade-East-Southern-Africa.pdf, [08.06.2023].

NAMIBIA ECONOMIST (04.03.2019): Minister warns against timber logging. Available from: https://economist.com.na/42391/environment/minister-warns-against-timber-exports/, [08.06.2023].

NAMIBIAN SUN (06.03.2017): Rumblings over debushing tender. Available from: https://www.namibiansun.com/news/rumblings-over-de-bushing-tender, [08.06.2023].

NAMIBIAN SUN (28.04.2017): Green Scheme project praised. Available from: https://www.namibiansun.com/news/green-scheme-project-praised, [08.06.2023].

NAMIBIAN SUN (20.06.2019): Chewing on the tobacco politics. Available from: https://www.namibiansun.com/news/chewing-on-the-tobacco-politics2019-06-20/, [08.06.2023].

NAMIBIAN SUN (21.06.2019): Simaata sings tobacco praises. Available from: https://www.namibiansun.com/news/simaata-sings-tobacco-praises2019-06-20/, [08.06.2023].

NAMIBIAN SUN (04.11.2019): Geingob courts timber harvesters. Available from: https://www.namibiansun.com/news/geingob-courts-timber-harvesters2019-11-04/, [08.06.2023].

NAMIBIAN SUN (24.02.2020): Mixed situation for timber trade. Available from: https://www.namibiansun.com/news/mixed-situation-for-timber-trade2020-02-24/, [08.06.2023].

Namibian Sun (03.03.2021): Green Scheme projects management reviewed. Available from: https://www.namibiansun.com/news/green-scheme-projects-management-reviewed2021-03-03, [08.06.2023].

NAMIBIAN SUN (04.06.2018): More teak to go. Available from: https://www.namibiansun.com/news/more-teak-to-go2018-06-04, [08.06.2023].

THE NAMIBIAN (17.12.2018): Timber harvests legal – !Naruseb. Available from: https://www.namibian.com.na/184128/archive-read/Timber-harvests-legal-%E2%80%93-Naruseb, [17.06.2021].

NAMIBIAN SUN (21.06.2019): Simaata sings tobacco praises. Available from: https://www.namibiansun.com/news/simaata-sings-tobacco-praises2019-06-20/, [08.06.2023].

NAMIBIAN SUN (12.07.2019): Rosewood harvesting unsustainable. Available from: https://www.namibiansun.com/news/rosewood-harvesting-unsustainable2019-07-11/, [08.06.2023].

THE NAMIBIAN (03.02.2020): Namibia to export 120.000 logs of timber. Available from: https://namibian.com.na/namibia-to-export-120-000-logs-of-timber/, [08.06.2023].

NAMIBIAN SUN (24.02.2020): Mixed situation for timber trade. Available from: https://www.namibiansun.com/news/mixed-situation-for-timber-trade2020-02-24/, [08.06.2023].

NCE (NAMIBIAN CHAMBER OF ENVIRONMENT) (2019): Position on harvesting hardwood timber in the north-eastern regions of Namibia. (NCE), Windhoek. Available from: https://n-c-e.org/sites/default/files/2019-03/NCE%20Position%20on%20Harvesting%20Hardwood%20Timber%20in%20NE%20Namibia.pdf, [08.06.2023].

NEW ERA LIVE (12.10.2015): Zambezi land availed Green Schemes. Available from: https://neweralive.na/posts/zambezi-land-availed-green-schemes, [08.06.2023].

NEWS24 (10.03.2015): Namibia: Youth Activists condemn land given to Chinese. Available from: https://www.news24.com/Africa/News/Namibia-Youth-activists-condemn-land-given-to-Chinese-20150310, [08.06.2023].

OCCRP (ORGANIZED CRIME AND CORRUPTION REPORTING PROJECT) (18.12.2020): ‘They are finishing the trees’: Chinese companies and Namibian elites make millions illegally logging the last rosewoods. Available from: https://www.occrp.org/en/investigations/chinese-companies-and-namibian-elites-make-millions-illegally-logging-the-last-rosewoods, [08.06.2023].

OXPECKERS (09.08.2017): State forest capture. Available from: https://oxpeckers.org/2017/08/state-forest-capture/, [08.06.2023].

THE NAMIBIAN (10.11.2005): Changes to Namibia’s forestry bill in pipeline. Available from: https://www.namibian.com.na/index.php?id=16549&page=archive-read, [17.06.2021].

THE NAMIBIAN (10.07.2017): Mafwe adviser defends timber harvesting. Available from: https://www.namibian.com.na/166708/archive-read/Mafwe-adviser-defends-timber-harvesting, [17.06.2021].

THE NAMIBIAN (01.03.2019): Rundu elite scramble for Kavango timber. Available from: https://namibian.com.na/rundu-elite-scramble-for-kavango-timber/, [08.06.2023].

THE NAMIBIAN (08.03.2019): Timber exports to China escalate. Available from: https://namibian.com.na/timber-exports-to-china-escalate/, [08.06.2023].

THE NAMIBIAN (01.03.2019): Rundu elite scramble for Kavango timber. Available from: https://namibian.com.na/rundu-elite-scramble-for-kavango-timber/, [08.06.2023].

THE NAMIBIAN (13.03.2019): Agriculture ministry plays hide and seek on timber harvesting. Available from: https://allafrica.com/stories/201903130225.html, [08.06.2023].

THE NAMIBIAN (03.04.2019): Chinese businessman arrested on corruption charge. Available from: https://allafrica.com/stories/201904030751.html, [08.06.2023].

THE NAMIBIAN (10.04.2019): Raw timber exports illegal. Available from: https://namibian.com.na/raw-timber-exports-illegal/, [08.06.2023].

THE NAMIBIAN (12.04.2019): !Naruseb’s efforts on timber questioned. Available from: https://namibian.com.na/narusebs-efforts-on-timber-questioned/, [08.06.2023].

THE NAMIBIAN (19.06.2019): Tobacco plant approval draws criticism. Available from: https://namibian.com.na/tobacco-plant-approval-draws-criticism/, [08.06.2023].

THE NAMIBIAN (25.07.2019): agribusdev sacrifices workers‘ salaries. Available from: https://namibian.com.na/agribusdev-sacrifices-workers-salaries/, [08.06.2023].

THE NAMIBIAN (19.09.2019): Authorities lift ban on timber transport in Namibia. Available from: https://namibian.com.na/authorities-lift-ban-on-timber-transport-in-namibia/, [08.06.2023].

THE NAMIBIAN (08.10.2019): N$ 100m fraud hits agriculture ministry. Available from: https://namibian.com.na/n100m-fraud-hits-agriculture-ministry/, [08.06.2023].

THE NAMIBIAN (15.10.2019): Agribusdev throws away N$ 800,000. Available from: https://namibian.com.na/agribusdev-throws-away-n800-000/, [08.06.2023].

THE NAMIBIAN (19.06.2020): Green schemes struggle financially. Available from: https://namibian.com.na/green-schemes-struggle-financially/, [08.06.2023].

THE NAMIBIAN INVESTIGATIVE UNIT (12.02.2019): Timber traders want to cut 195,550 trees. Available from: https://investigations.namibian.com.na/timber-traders-want-to-cut-195-550-trees/ [08.06.2023).

THE VILLAGER (30.10.2018): Tobacco and Maize project not implemented – Shifeta. Available from: https://www.thevillager.com.na/articles/14149/tobacco-and-maize-project-not-implemented-shifeta/ [08.06.2023].