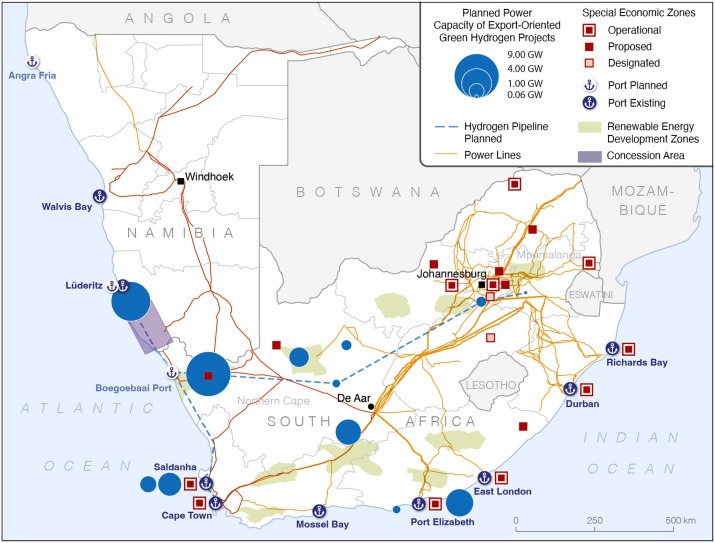

Since 2006, the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA) cuts across very distinct rural landscapes of Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Despite its declared goal to harmonize policies, strategies, and practices, current land use patterns in the five national subzones of the KAZA are historically determined outcomes of interactions between people, wildlife, and natural vegetation dynamics in heterogeneous political, economic, cultural, and biophysical settings. After decades of conflict, ambitious conservation strategies were first formulated in the 1990s by the South African Development Community (SADC). In the early 2000s, however, the completion of the bridge between Zambia and Namibia greatly improved transport connectivity along the Walvis Bay-Ndola-Lubumbashi Development Corridor (WBNLDC).

Despite considerable investments in conservation and regional development, poverty incidence remains high in KAZA, with population growth rates at 2% annually at comparatively low population densities. KAZA accommodates Africa’s largest elephant population (ca. 216 thousand), which is relatively stable though herd monitoring remains a challenge. Local complaints about increasing rates of human-wildlife conflict could be due to changing human and animal population distributions, but may also result from changes in animal behavior or agricultural practices. Given frequent fires, bush-encroachment, and illegal extraction of valuable hard-wood trees, rates of woodland cover change are highly volatile with no dominant trend, despite continuous degradation of natural vegetation. At the same time, some Southern African countries gear up for REDD+, which would add to the complex incentive mix governing the current land-use system.

Thinking about the future of people, wildlife, and trees in a trans-frontier conservation area that stretches across five countries and is cut in half by an ambitious development program, requires integrating multiple theoretical perspectives in what has been called a “middle range theory” of land use (Meyfroidt et al. 2018). For some types of land systems in the region, Chayanov’s approach to describe peasant agriculture and semi-commercial livestock systems might be appropriate to understand the observed slow process of natural landscape degradation. However, a better understanding of how traditional rules and norms interact with changing social-ecological system dynamics (including soil and aquatic ecosystems) is needed in order to design appropriate access & benefit sharing mechanisms as human-wildlife conflicts increase in response to population growth. At the same time, land rent and induced intensification theories would appear helpful in explaining the emergence of specialized intensified agriculture as a result of both private and public initiatives.

Whether or not conservation in the KAZA region will benefit from a ‘forest transition’ aided by rural-urban migration and diversification of the rural economy, for example through tourism, will still depend more on the future development pathways of the individual KAZA partner countries rather than on the outcomes of trans-frontier cooperation in conservation and development.

Meyfroidt, P., Chowdhury, R. R., Bremond, A. de, Ellis, E. C., Erb, K.-H., Filatova, T., Garrett, R. D., Grove, J. M., Heinimann, A., Kuemmerle, T., 2018. Middle-range theories of land system change. Global Environmental Change. 53, 52–67.

by Jan Börner, Wulf Amelung, Liana Kindermann, Anja Linstädter, Maximilan Meyer und Alexandra Sandhage-Hofmann