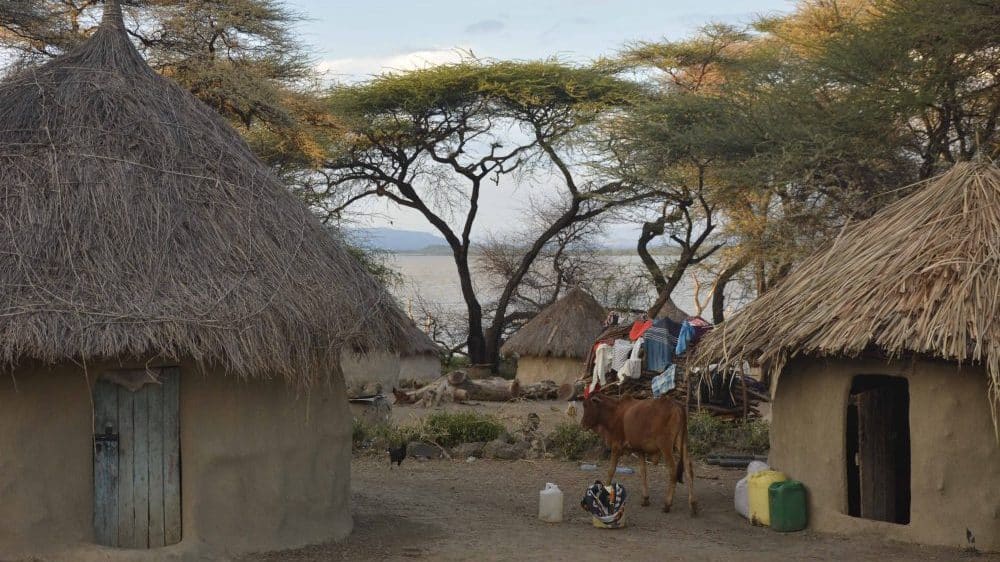

The Il Chamus, Maa-speaking agro-pastoralists who inhabit the lowlands south of Lake Baringo, are concerned about their future. They have for long dealt with difficult climatic conditions, suffered occasional raids from neighboring ethnic groups, and claimed to have faced marginalization from the Kenyan government. However, when anthropologist Peter Little conducted fieldwork near Lake Baringo in 2017, Il Chamus elders he engaged with were not concerned about acquiring funding assistance to boost development projects. Rather, they sought access to colonial-era maps in which colonial administrators outlined “ethnic” boundaries in the region, i.e. boundaries of “native reserves” that separated different ethnic groups. The elders sought to refer to these once-controversial colonial maps to legally prove that their neighbors, with whom they were in an increasingly violent conflict in the last 15 years, were overstepping boundaries in search of receding grazing lands (Little 2019).

Our research in Baringo County, a part of the “B04: Projecting Futures” subproject, also suggests the renewed significance of boundaries, conceptualized as zones of contact and conflict, in contexts of demographic pressures and the increasing importance of access to rangelands and arable land. Many of our Il Chamus research participants have been displaced from their homes as a result of intensifying attacks from neighboring groups. In addition, many complain about the spread of the invasive prosopis juliflora plant which has taken over some key grazing areas. Il Chamus elders interpret both of these trends as land encroachment. Many of our interlocutors feel increasingly squeezed by these environmental pressures and insecurity. Conflicts over access to land and over boundaries with other ethnic groups are central to people’s perception of an uncertain future.

In our research, we observe attempts to find ways to negotiate these boundaries. In recent years, Il Chamus families have gradually sought to carve out spaces to return to their homesteads in contested border areas from which they were displaced and call on government security forces to provide assistance. Moreover, many young men in border areas are eager to join the government-endorsed local National Police Reserve defense force, which allows them to fulfill the role of “defending the community” from outside attacks while also receiving a small (albeit insecure) remuneration and gaining respect as employees of the state. Most strikingly, certain elders meticulously maintain detailed records of names of families forced to vacate their homes, of the damages inflicted on their belongings, and of the Il Chamus names of towns and villages in contested areas that were “corrupted” by the neighboring ethnic groups.

Il Chamus leaders and ordinary men and women are thus highly invested in (re)claiming land and (re)constructing boundaries with other ethnic groups as part of efforts to imagine and construct a more stable and predictable future. Some new boundaries emerge, and some old ones are being reinforced. Negotiations over boundaries between ethnic groups emerge as crucial for future-making in contexts of insecurity and environmental pressures.

Reference

Little, Peter D. 2019. “When “Green” Equals Thorny and Mean: The Politics and Costs of an Environmental Experiment in East Africa.” African Studies Review 62(3):132–163.

By: Uroš Kovač