In the introduction to their edited volume Elusive Promises: Planning in the Contemporary World, Simone Abram and Gisa Weszkalnys (2013) introduce their understanding of modern planning as “an assemblage of activities, instruments, ideologies, models, and regulations aimed at ordering society through a set of social and spatial techniques” (ibid: 3). This open definition is in line with earlier works that discuss the relationship between planning and governmentality that focuses on subtle (and blatant) forms of power and control, such as James Scott’s Seeing Like a State (1998) and others, to which they refer briefly. The main conceptual contribution of Abram and Weszkalnys, however, is their call for a stronger temporalization of planning, hence demanding a shift of focus from the spatial domain of planning to the temporal domain. Whereas Scott and others show how states employ techniques of planning to ultimately make their populations legible by ordering space, Abram and Weszkalnys emphasize the effect of planning for the experience of temporality of the subjects that are confronted with plans from governmental actors. As a first step, Abram and Weszkalnys propose to understand planning as practices that manage the present by tying it to the future (2013: 11). Hence, practices of planning are a particular kind of future-making. Further, they understand planning as promise-making. Promises tie promisors (states) and promisees (citizens) together and promises are made in specific contexts. Unfulfilled promises harm the relationship between promisors and promisees and elusive promises make promisees stuck in a state of not- quite- yet or, as Abram and Weszkalnys frame it, in a state where the goals remain always “slightly out of reach” (ibid: 3).

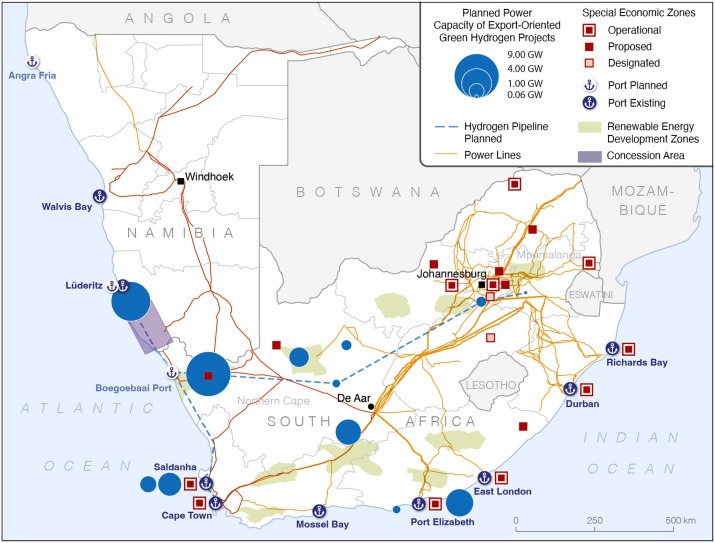

As the CRC is concerned with large-scale plans and visions such as KAZA, LAPSET, or different national visions for 2030, Abram’s and Weszkalnys’ edited volume promises, and I think it does so without being elusive, to be of help for conceptualizing experiences of being stuck in the not- quite- yet. Such experiences were common at least for my interlocutors in Namibia’s Zambezi region. Though I hoped for a bit more conceptual ‘flesh’ about how to temporalize planning, the purpose of an introduction for an edited volume is not to preempt all conceptual work; it is rather to prepare the conceptual ground for empirical examples that demonstrate the diversity of how different practices that (promise) to prepare the future from the toolbox of modern bureaucratic statecraft shape citizen’s senses of temporal entanglement with the world. As such, the introduction certainly succeeded, and I look forward to reading the contributions to the volume.

By: Joachim Knab. Institute for African Studies, University of Cologne.

References

Abram, Simone & Gisa Weszkalnys (eds). 2013. Elusive Promises: Planning in the Contemporary World. New York: Berghahn.

Scott, James C. 1998. Seeing like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition have Failed. New Haven, London: Yale University Press.